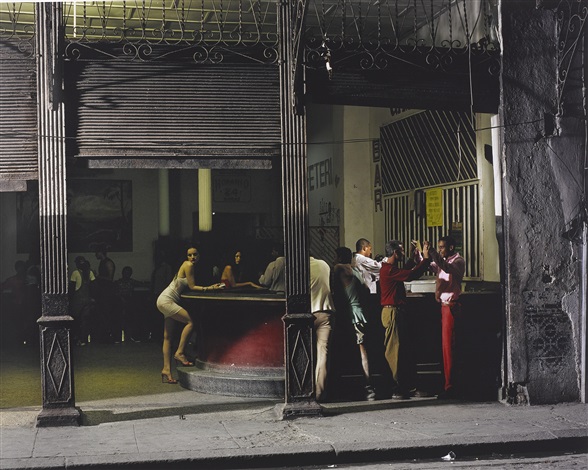

The productions were lavish as the magazine commissioned Philp-Lorca diCorcia to travel to exotic places to shoot high fashion with the supermodels of the days. Cuba, Russia, Brazil, Dior, Chanel, Balenciaga, amazing crews… the producer that I was then was envious (and in awe of the resulting images).

His fashion series lead me to his fine-art work, which only deepened my love for him. I’ve since bought pretty much every one of his books (and he has quite a few!).

Born in 1951 in Connecticut in a prominent Italian-American family (his father was a successful architect), Philip-Lorca diCorcia’s first photographs were of relatives and friends, taken in their homes.

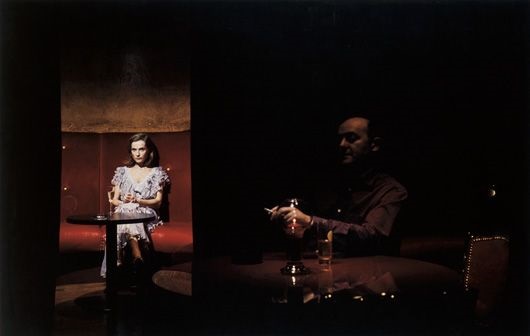

While the situations are rooted in everyday banality (as in the photograph of a man looking into an open fridge), his use of light and the stillness of his subjects bring mystery to the images.

Why is this man peering so forlornly into his fridge? Why does he look so transfixed by it, as if hypnotized?

Philip-Lorca DiCorcia’s work mixes documentation and fabrication: he favors real-life subjects but bathes them in mystery.

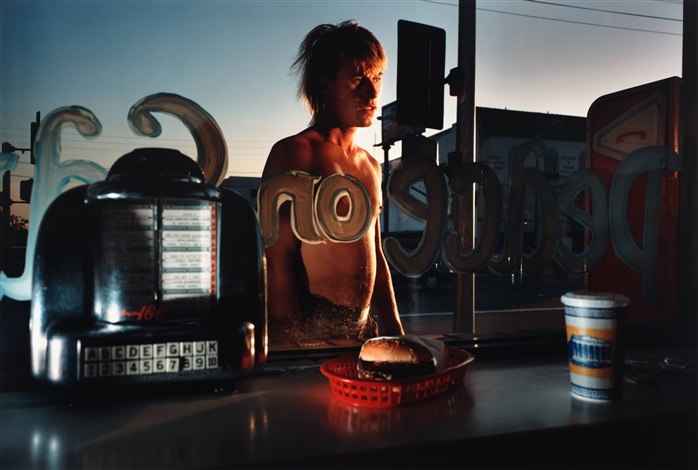

One of his most famous series is the “Hustlers” project, which consists of formal portraits of male hustlers in Los Angeles. (One of the images opened this article.)

Philip-Lorca diCorcia carefully planned every detail of the shoot, from the locations to the lighting and poses. The resulting images are infused with melancholy; his subjects become tragic figures, lost souls who stood just long enough in front of a camera before disappearing back into the shadows.

For “Streetwork” and “Heads,” Philip-Lorca diCorcia chose a completely opposite approach: he set up a camera on a tripod in Times Square, New York, attached lights to scaffolding across the street and took pictures of unsuspecting strangers. Although nothing is controlled, his lighting and cropping create a narrative around these solen moments. Time is suspended, and his subjects appear alone, even when they are in a crowd.

Philip-Lorca diCorcia was later sued by one of the pedestrians he photographed. Erno Nussenzweig, an Orthodox Jew, argued that his privacy and religious rights had been violated by both the taking and publishing of his photograph, which happened without his consent. Because prints were later sold in a gallery, he felt the image was commercial (for which subjects need to give their consent), not artistic.

The judge dismissed the lawsuit as she found the project was indeed art and therefore protected by the First Amendment. Selling limited edition prints does not negate the artistic character of a work – the case was an important one for American photographers.

No matter the setting or subject, from downtrodden denizens of the street to anonymous pedestrians in a crowd to glamourous fashion models, Philip-Lorca diCorcia’s images have all a haunting quality that stays with you.

© Philip-Lorca diCorcia

Disclaimer: Aurelie’s Gallery does not represent Philip-Lorca diCorcia. My “Photographers I love” series is purely for inspiration and to encourage discussion.