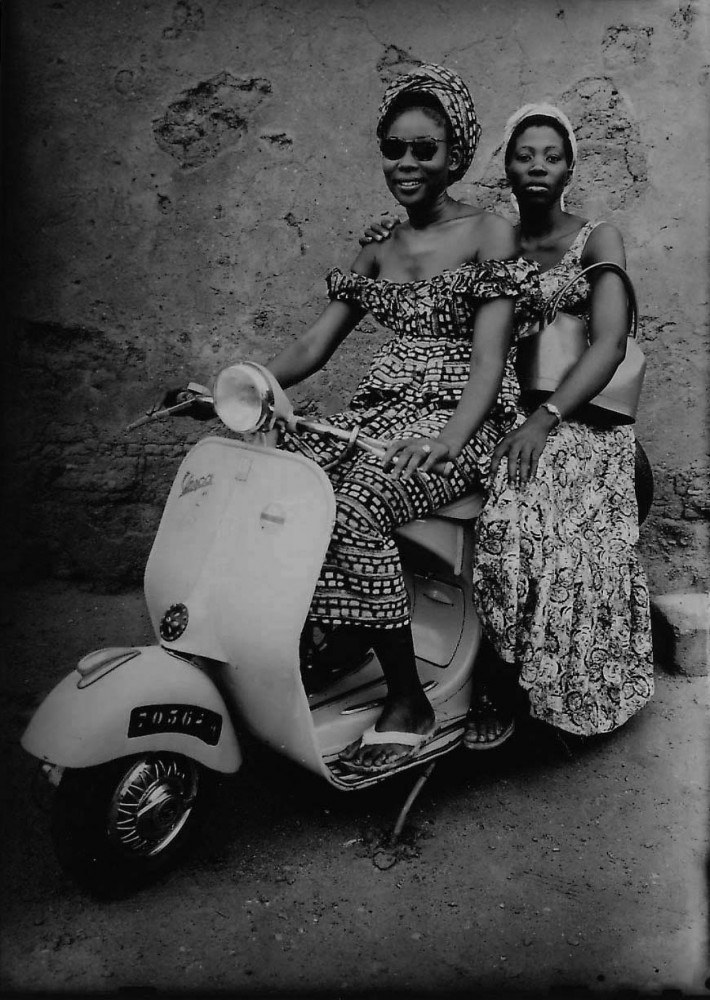

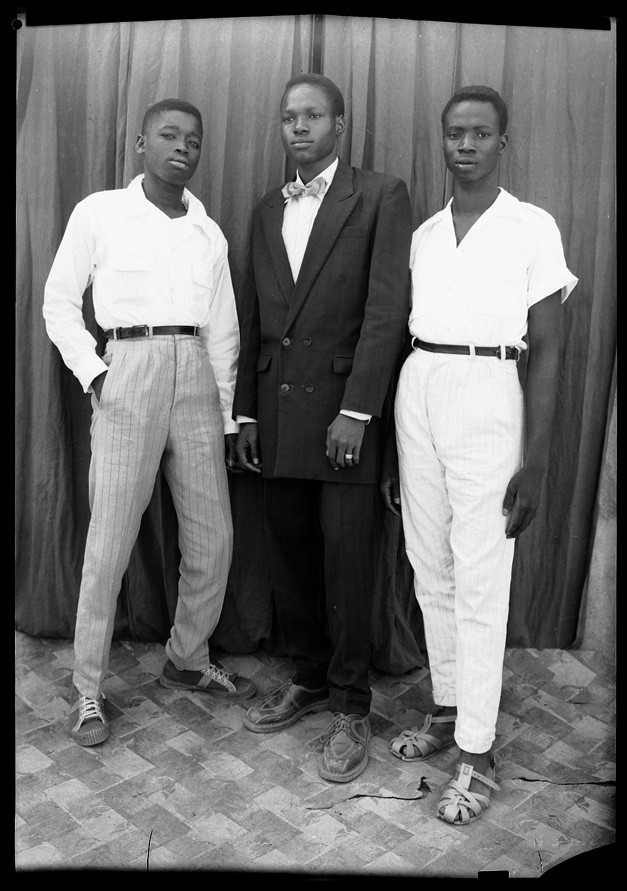

I love how Seydou Keita’s images use the formality of 19th-century bourgeoisie portraiture in an unmistakably African setting.

Seydou Keita ran his studio in Mali’s capital, Bamako, from 1948 to 1962. He captured not only portraits but a changing society, as his country went from being a French colony to being independent. His black and white images endured the test of time and are now celebrated for their formal beauty and humanity.

Born in 1921 in Bamako, Seydou Keita came from a large family and first worked as a carpenter, following his father’s footsteps. After an uncle gifted him a camera, he learned the craft from friends and his own experimentations. What started as a hobby soon became his life and livelihood.

His studio quickly gained fame in Mali and neighboring countries in West Africa. His use of props and backdrops was unusual for the time and helped set him apart. A genius at marketing, Seydou Keita stamped his photographs “Photo Keita Seydou,” which helped spread his name far and wide. He also hired assistants to find clients all over Bamako, ensuring a steady stream of work.

You can chart Mali’s social evolution through his images as the country went through an extraordinary economic boom and modernization during Seydou Keita’s time. While his earlier photographs show men and women in traditional garbs, later work have them in suits and Westernized dresses. His subjects flash signs of their success, from purses or watches to a scooter or a car (even though some of these props were at times borrowed from the photographer!). Seydou Keita shows an idealized version of his subjects and the world around him.

As his access to professional gear was limited, Seydou Keita used mostly daylight. In his backyard turned studio, he hung fabric, echoing the rich velvet drapery found in classic paintings of noblemen. In Seydou Keita’s settings, velvet drapes are replaced by “wax”, a cotton cloth with batik-inspired printing and commonly found in West Africa, turning a European art tradition on its head.

Seydou Keita patiently directed his subject, showing them examples of past portraits and directing them toward the best pose and attitude. He often took only one frame as his clients could not afford more. (One frame! Think of this next time you fill your 5mg card shooting the same thing for 2 hours!)

In 1962, after Mali gained independence, Seydou Keita was offered a job as the official government photographer – an opportunity he couldn’t pass. He closed his studio a year later. His work stayed mostly untouched for 30 years before being “discovered” and exhibited in the West in the 1990s.

Seydou Keita is now regarded as the father of African photography. His images are iconic representations of West African life and culture in the second half of the 20th century. His legacy lives on as his work continues to inspire a new generation of photographers who aim to capture the diversity and richness of African life.

© Seydou Keita

Disclaimer: Aurelie’s Gallery does not represent Seydou Keita. My “Photographers I love” series is purely for inspiration and to encourage discussion.