Nan Goldin’s photographs are not always easy to face. They show hardship, violence and pain. But they also, and more importantly, show life – the good, the bad, and the ugly of it. I love her work because she is unafraid, and that’s too rare a quality in this world.

Nan Goldin grew up near Boston in the 1950s. The Norman Rockwell image of suburban middle-class life imploded when her older sister committed suicide when Goldin was 11. Her sister wanted to live freely, but the loosening of social mores and the sexual revolution the pill introduced in the 60s hadn’t happened yet. Nan Goldin is a product of the liberation her sister never saw.

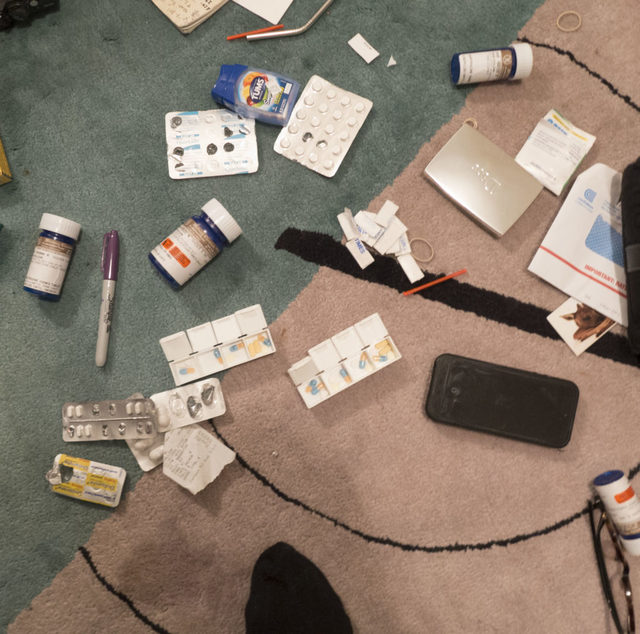

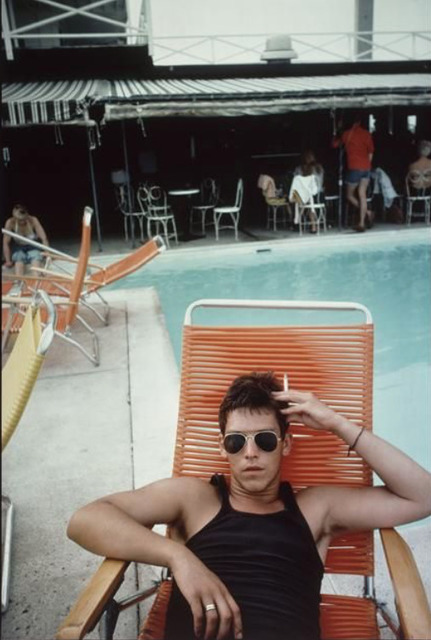

She started documenting her friends as a teenager, capturing unfiltered moments of intimacy and vulnerability. Rebelling against the fallacy and strict patriarchal rules of her world, she gravitated towards outsiders and marginals. Drugs sang their siren song, carried by The Velvet Underground and other bands. The appeal was irresistible, especially in a repressed society. Goldin viewed junkies as romantic figures and followed their path for a while. She eventually saw them for what they were – tragic figures, people lost to forces stronger and darker than themselves – but she never judged them.

In 2007 she revealed with her usual honesty that she was recovering from an opioid addiction. She turned her personal struggle into a ferocious fight against the Sackler family and their company, Purdue, which produced and pushed oxycotin. Goldin targeted museums and universities that accepted their money and shed light on the ugly side of philanthropy. Her activism bore fruit: in December 2021, the Met Museum in New York removed the Sackler name from its exhibition halls.

Her photographs act as a private diary to remember and pay homage to the people in her life, people who are often shunned and ignored by society. You feel her obsession with memory, her fight to freeze and keep moments so they don’t disappear like too many of her friends have over the years. From documenting drug addictions to the desolation AIDS brought onto her friends, she often found herself on the bank of the River Styx. Would she had had documented so extensively her life if death had not been such a constant presence around her?

Nan Goldin doesn’t shy away from the pain that sometimes comes with being alive. I remember her show at MoMA and seeing with her (in)famous self-portrait where you see her with a black eye after an argument with her boyfriend. I find the image difficult to look at – the idea of getting punched in the face by the person I love is pretty terrifying for me – but there she stood, upright and strong, flaunting expectations of decorum or victimhood.

“I used to think that I could never lose anyone if I photographed them enough. In fact, my pictures show me how much I’ve lost.” Nan Goldin

Her photographs are often very intimate and raise questions about voyeurism and exploitation. I don’t think anyone can accuse Nan Goldin of being an opportunistic voyeur – these are her people, her friends, her tribe. She shares these moments with them; she lives their pains and joys. Her subjects have veto power over what she exhibits, which as it should be.

Although she belongs to that scene, what about us? We are the ones looking at these private moments hanging on a wall of a gallery or museum. Aren’t we the voyeurs?

© Nan Goldin – Disclaimer: Aurelie’s Gallery does not represent Nan Goldin. My “Photographers I love” series is purely for inspiration and to encourage discussion.