Diane Arbus transformed photography by turning her lens toward the downtrodden and forgotten, favoring “freaks” over the polite society into which she was born. Hers is a tragic tale, one of an unwavering woman who pursued her art against all odds.

EARLY LIFE

Born Diane Nemerov on March 14, 1923, in New York City, USA, she grew up in an affluent family. Her father ran Russek, a successful department store, while her mother hailed from a wealthy and influential family. Their money insulated young Diane, even while the Great Depression destroyed countless lives around them. While many in her privileged circle clung together and showed little interest in the less fortunate, being cut off from the world had the opposite effect on Diane. She spent the rest of her life in search of the reality she was forbidden to see as a child. Diane Arbus later said about her privileged childhood, “It was like being a princess in some loathsome movie… and the kingdom was so humiliating.”

The Nemerov household offered both freedom and tradition. Her parents were not very involved in raising their children, as was often the case then in high society. Her father was busy with work, and her mother navigated between an active social life and bouts of depression. Diane was exposed to arts and culture, nurturing her curiosity and creativity. Her artistic gifts were apparent early on, and her father encouraged her to study painting and drawing. (Interestingly, she later befriended Richard Avedon, another photographer known for his portraits, who was also born into a family of luxury retailers.)

PHOTOGRAPHY BEGINNINGS

Society’s expectations for a young lady of her class narrowed her freedom – a weight she rebelled against early on. Diane fell in love at 14 with one of her father’s employees, Allan Arbus, who worked in Russek’s art department. Her parents disapproved of this misalliance, but Diane continued dating Allan in secret. In 1941, at the age of 18, they married against her parents’ approval. How much was it for love? How much was it to flee her suffocating milieu? I’m not sure it matters – the courage and fortitude she showed then defined the rest of her life.

They had two daughters and from 1946 to 1956 ran “Diane & Allan Arbus,” a photography studio for fashion and advertising clients. Diane worked as a stylist and art director, while Allan had the more prestigious (and manly) role of photographer. Despite their success, they both came to loathe the commercialism of their work. Allan encouraged her to take her own pictures, and she later credited him as being “[her] first teacher.” But she ultimately found herself caught in yet another insulating environment. Her safe and predictable life was not what she had dreamed of when she fled her family.

Their respective discontent and Diane’s episodic depression put a strain on their marriage. They stopped working together in 1957 and separated two years later. When the norm was to be (and stay) married, Diane Arbus had the courage to find her path. Although they remained close and Allan supported her efforts, she found herself alone with two young children to care for. Everything piled up on her at once: she had to find her voice as an artist while rebuilding her life as a woman and mother.

FINDING HER PATH

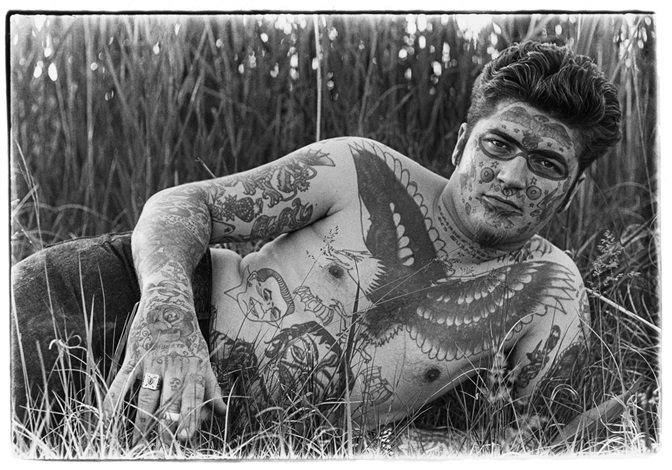

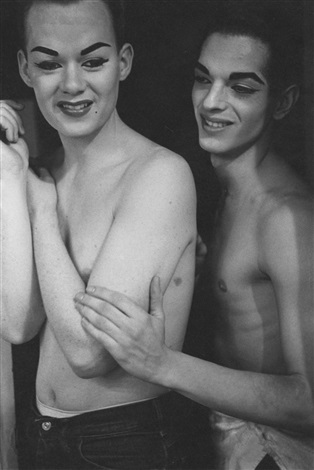

Diane Arbus studied with documentary photographers Berenice Abbott and Lisette Model. She credited Model with making it clear to her that “the more specific you are, the more general it’ll be.” Model also helped her identify what she truly wanted to photograph. With her sheltered life squarely left behind, Diane Arbus began her search for truth and reality. Immersing herself in portraiture, she captured subjects often considered unconventional or outside of “normal” society. She photographed rich old ladies in the Upper East Side of Manhattan and drag queens performing in underground clubs. Her lens became a bridge between the ordinary and the extraordinary. Her images are at times disturbing and always unflinching. They explore how personal identity is a social construct. Her subjects vary but all wear some form of a mask, whether it be men wearing makeup, performers in their costumes, or baby-faced teenagers in grown-up clothes. Her portraits focus on what she called “the gap between intention and effect.” The distinction between what we try to communicate about ourselves and what is perceived by others is a recurring theme in her work.

In late 1959, Diane Arbus began a relationship with the art director and painter Marvin Israel that would last until her death. He became one of her most fervent champions, advising and encouraging her, and he introduced her to people who could help her. Around 1962, she left behind her 35mm Nikon camera and its grainy images and switched to a twin-lens Rolleiflex, which captured crisp square images. She explained this transition, saying, “In the beginning I used to make very grainy things… But [after a while], I began to get terribly hyped on clarity.”

DIANE ARBUS AND HER SUBJECTS

The square format of her prints became part of her signature. Their tight focus helped her emphasize humanity over trappings. The subject is front and center, nothing else really matters. Diane Arbus pioneered the use of flash in daylight, which, by separating the person from the background, adds a dose of surrealism to her images. “For me, the subject of the picture is always more important than the picture,” she said. “And more complicated.”

Her new medium-format camera was held at the waist. She would simply look down into the viewfinder, which allowed her to maintain eye contact with her subjects while shooting. Not having the photographer hold up a camera to their face must also have helped people relax and forget they were being photographed. The intimacy of this setup helped her establish a more direct connection with the people in front of her lens.

Diane Arbus is indeed famous for forming strong personal relationships with her subjects. She even rephotographed a few of them throughout the years. And supposedly slept with some of them [I don’t think the lurid allegations would elicit much response had she had been a man … but I digress]. She was alternately described as shy and sweet or as tough and cold. Her ability to relate to her subjects, along with her openness and vulnerability with them, set her apart. Her intense relationship with her subjects became central to her work. Although her images can seem merciless, her writing clearly shows how much she cared for the people she photographed.

CONTROVERSY AND CHALLENGES

Diane Arbus further engaged with life at the margins of 1960s America. She photographed circus performers, nudists, the elderly, and the mentally or physically handicapped… People who were often ignored by the art world then. The intimacy of her images confronted viewers with their biases. As her photographs gained recognition, they also sparked debates about boundaries and artists’ responsibility. While some attacked her for invading the privacy of her often-disadvantaged subjects, others lauded her for exposing uncomfortable truths. Her images were either seen as empathic or harsh and voyeuristic. But why can’t she be voyeuristic AND empathic? I’m not sure the two are so mutually exclusive. And aren’t we all a bit voyeur? She might have gone further than most, but the (uncomfortable) truth remains: we all like to watch.

In 1965, the Museum of Modern Art included three of her images in its “Recent Acquisitions” show. Diane Arbus was apprehensive and feared the public reaction. Her concerns were validated when she learned museum staff had to wipe visitors’ spit off her portrait of a drag queen in curlers. People felt threatened when looking at her images. She showed things most people were told to avoid. She found the attention hard to cope with and remained anxious for the rest of her life.

To support herself and her kids, Diane Arbus took assignments for magazines such as Esquire and The Sunday Times Magazine. She also taught photography at the Parsons School of Design in New York and RISD in Rhode Island. Constant money problems added pressure to her already complicated life. Juggling between editorial jobs, higher education establishments, and her art practice was a struggle. It was also rare at the time. It’s common today for artists to work in different fields but that was frowned upon in the 1960s when people tended to stay in their lane. She challenged the norm here again.

In 1967, MoMA included her in “New Documents,” a major show about documentary photography. Her work appeared alongside Garry Winograd and Lee Friedlander, two celebrated artists. The show was polarizing, and Diane Arbus was again accused of exploitation and voyeurism. Now labeled the “freak photographer,” she saw her editorial jobs dwindle as magazines became wary of the controversy surrounding her. The show that should have established her firmly in the art world unwittingly further marginalized her.

Despite the pressure, Diane Arbus remained steadfast. For her, photography was a powerful medium for exposing the truth, no matter how uncomfortable it may be. In an interview, she remarked, “I really believe there are things nobody would see if I didn’t photograph them.”

STRUGGLES AND RECOGNITION

Diane Arbus had the idea to create a limited edition of ten of her photographs, placed in a clear plastic box. She aimed to sell each set for $1,000, but there was no real market yet for fine art photography (especially when its subject matter was deemed “unsavory”). She managed to sell only four portfolios during her lifetime, but often had to sell individual prints for a mere $100. In 2023, one of these early sets sold for £1 million at Christie’s NY – a world record price for the photographer. More importantly, the work turned Artforum’s editor-in-chief into a convert. He had long been a photography skeptic and never agreed to show it in the famed art magazine. But after meeting Diane Arbus and seeing one of her boxes, he said, “One could no longer deny photography’s status as art. What changed everything was the portfolio itself.” In 1971, Diane Arbus went on to become the first photographer to be featured in Artforum.

But the recognition couldn’t erase the hardship. Diane Arbus suffered from depression and hepatitis, an illness that further weakened and depleted her. She also found herself in an untenable position, caught between her need for money and her fear of public attention. It all came to an end when she committed suicide on July 26, 1971; she was 48 years old. A year later, her work was included in the Venice Biennale, a seminal art event. Her photographs were described as “the overwhelming sensation of the American Pavilion.” She was the first photographer ever featured there.

DIANE ARBUS’ LEGACY

Although tragic, there’s a real risk that her death overshadows her work. To see her as a depressed figure who reveled in the abject denies her strength. To dismiss her work as morbid means we don’t see her for the humanistic photographer she was. She created a new form of documentary portraiture, one that is deeply personal and intimate. Her photographs show as much the vulnerability of her subject as her own frailty. Nan Goldin is her direct heir, exploring people in the margins of society and her relationships with them. The two artists share the same refusal to judge their subjects.

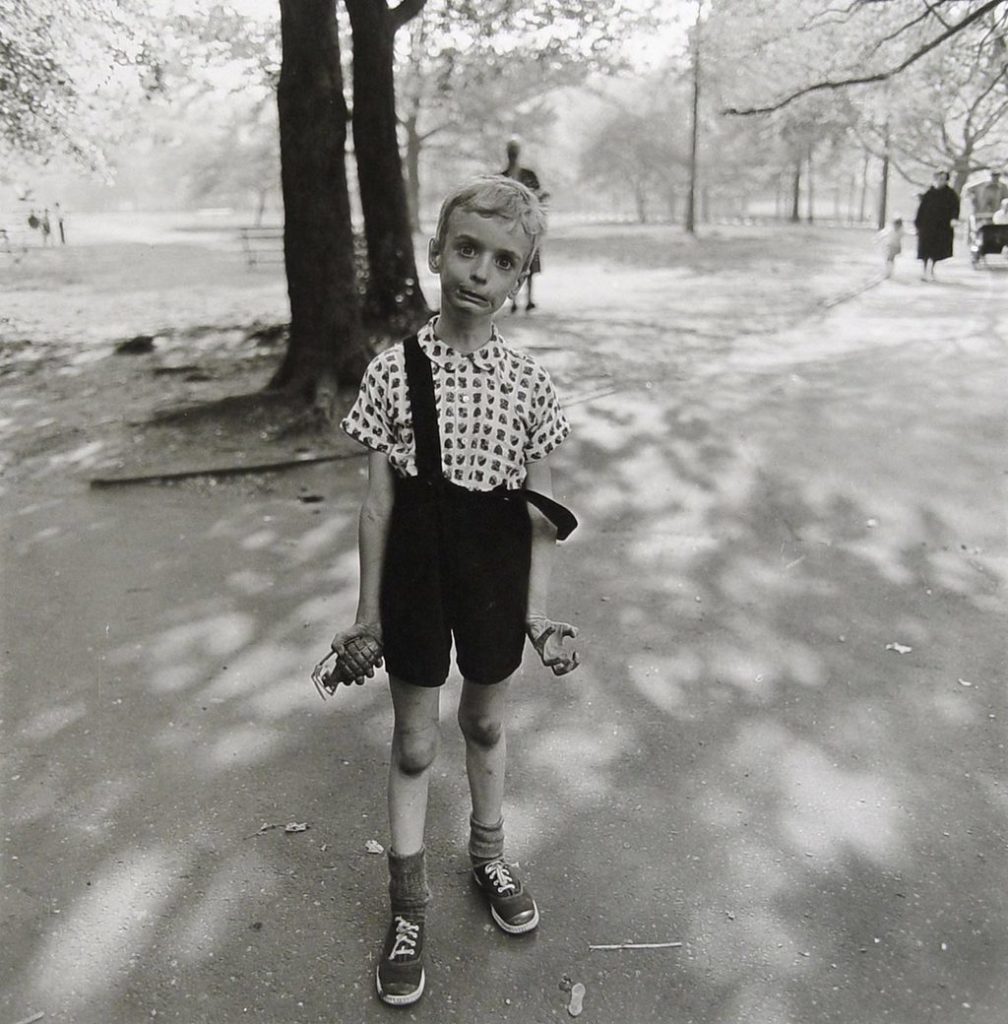

I love what Norman Mailer said about Diane Arbus, “Giving a camera to Diane Arbus is like putting a live grenade in the hands of a child.” What I love most is that, although he meant it in jest (he was supposedly displeased with the portrait she took of him), his dismissive quip betrays a truth. Diane Arbus was indeed a force to be reckoned with.

Painfully controversial in her lifetime, Diane Arbus was accepted only after her death. She is now considered one of the most influential artists of the 20th century. Her work continues to resonate with modern audiences. Her intimate portraits challenge preconceived notions of a photographer’s place and distance from their subjects. They question our voyeuristic nature and the predatory nature of photography (and of all art forms, really – if not of life itself!). Diane Arbus’ story is one of rebellion, resilience, and artistic brilliance. From her privileged upbringing to groundbreaking work defying societal norms, she remains an inspiration to many.

“My favorite thing is to go where I’ve never been.” Diane Arbus

PS: I recommend Fur: An Imaginary Portrait of Diane Arbus, a 2006 movie with Nicole Kidman. Though not a strict biography, fiction can reveal reality.

© The Estate of Diane Arbus. Disclaimer: Aurelie’s Gallery does not represent Diane Arbus. My “Photographers I love” series is purely for inspiration and to encourage discussion.