Photographers I Love: Lee Miller

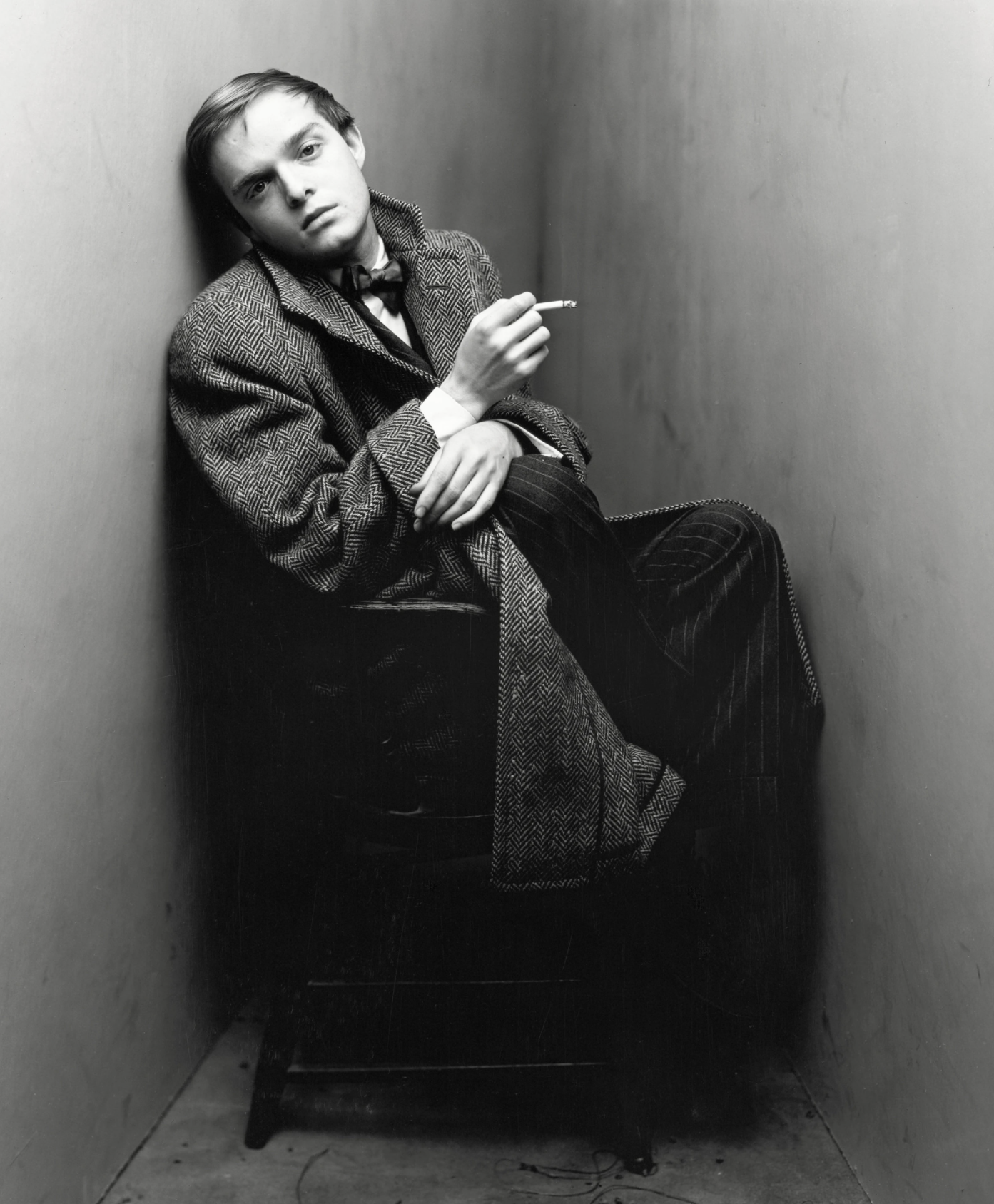

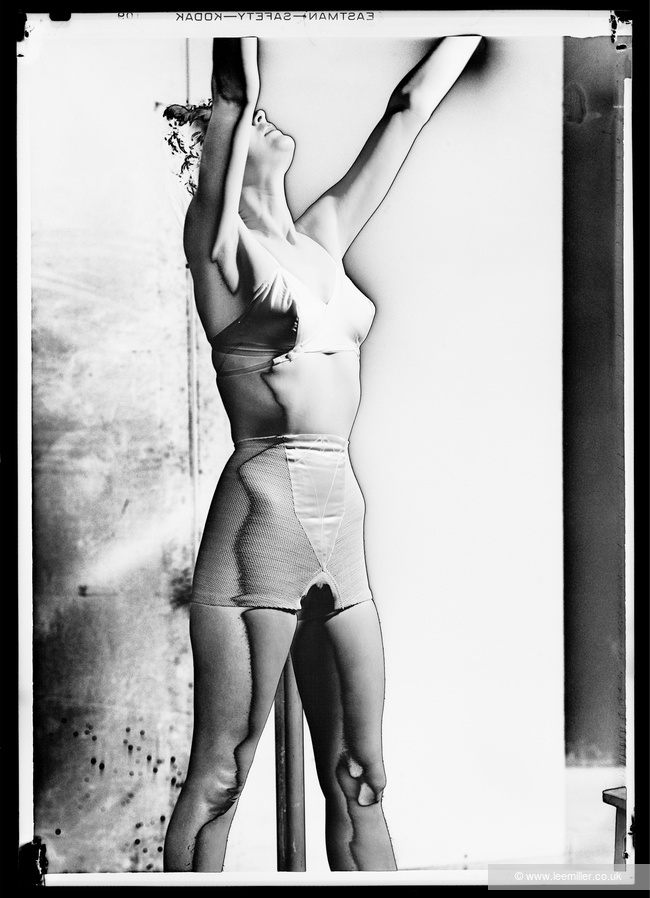

NOTE: The Lee Miller Archives graciously loaned me 2 images to illustrate this article. If you want to see more of her work, please go to www.leemiller.co.uk.

For too long, Lee Miller was known solely as a muse (and lover) to Man Ray, the beautiful face behind some of his most famous photographs. She seemed to have lived a charmed life – a model for US Vogue turned It Girl in Paris’ 1930s surrealist art scene. But thanks to her son, she has recently come to be seen as a full artist in her own right. Her extraordinary life even became the subject of a Hollywood biopic starring Kate Winslet.

EARLY YEARS

Born in 1907 in Poughkeepsie, New York, USA, Elizabeth “Lee” Miller learned about photography through her father, an amateur shutterbug who taught her the rudiments of the craft. Her seemingly happy and privileged childhood was shattered when a family relative raped her when she was only 7. The resilience and strength she displayed later in life are rooted in that trauma (but, too often, trauma makes you strong, until it destroys you).

Lee posed often for her father, sometimes nude, well into her teenage years. Many wonder what this early sexualization might have done to her psyche, adding to the trauma of being raped. Perhaps not surprisingly, Lee was restless and was expelled from numerous schools. She found catharsis in the arts, studying theater lighting and set design, life drawing and painting.

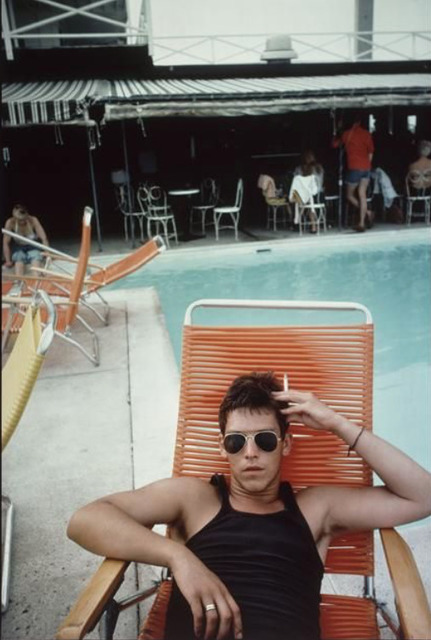

MODELING DAYS

At 19, according to legend (as told by Lee’s son, Antony Penrose), Lee nearly got run over in a busy Manhattan street. Condé Nast, the publishing magnate, came to her rescue; she fainted in his arms… and a few weeks later was on the cover of Vogue! [Although lovely, I somewhat doubt the veracity of this tale. I picture Lee more likely throwing herself into traffic to catch Nast’s attention than playing damsel in distress! But who knows? Life can be stranger than fiction.]

Lee was beautiful and became a sought-after model and It Girl, but the glamour faded quickly and left her wanting more. Unlike many of her contemporaries, modeling was a stepping stone, not the destination. The unfortunate (and unauthorized) use of her image in an ad for Kotex pads precipitated her decision: as fashion turned its back on her for this unsavory connection, she left fashion behind to return to her true love art.

"I'd rather take a photograph than be one." Lee Miller

BECOMING A SURREALIST

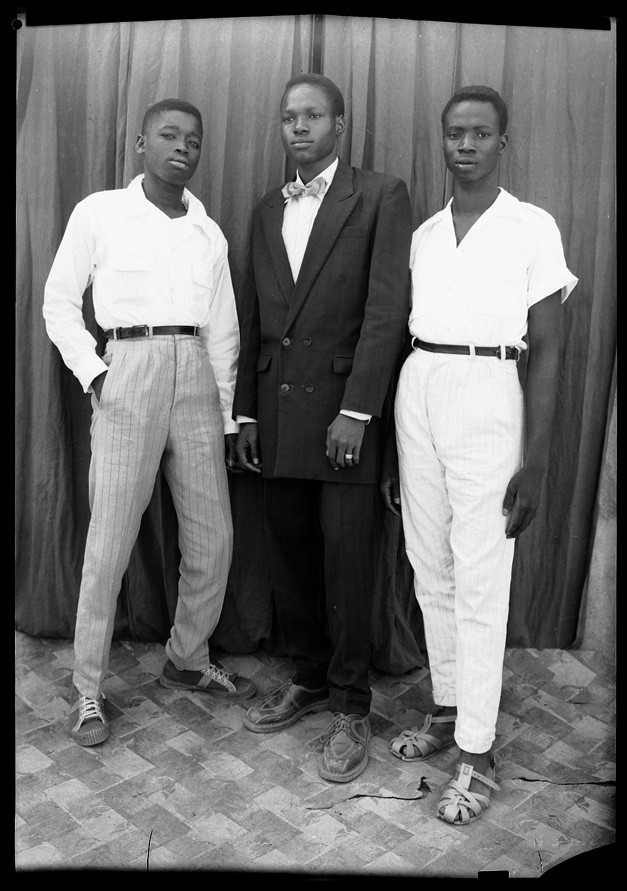

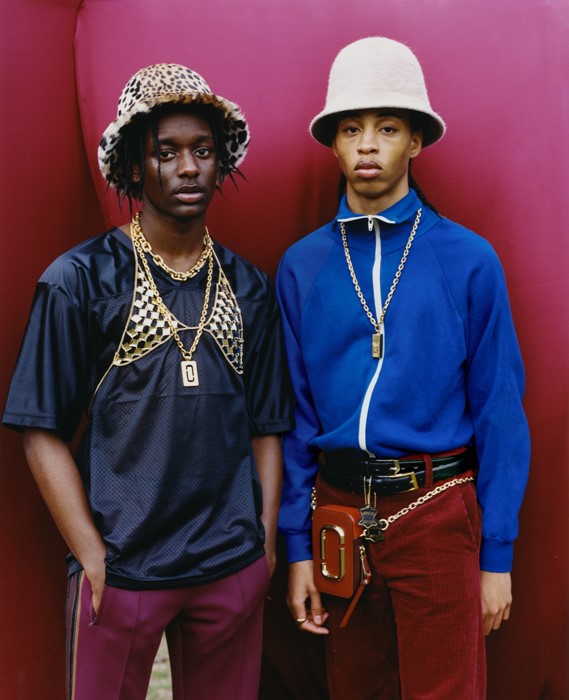

In 1929, aspiring to become an artist, Lee moved to Paris, then the center of the art world. She quickly met everyone who was anyone, from Picasso, Joan Miro, to Jean Cocteau (for whom she starred in Blood of a Poet, his 1932 film) and formed lifelong friendships with fellow artists.

When later interviewed about how she became a photographer, she explained, “I thought the best way was to start out studying with one of the great masters in the field, Man Ray.” Armed with a letter of recommendation from Edward Steichen for whom she had posed, she went to see the famous artist. Although Man Ray didn’t take students, he eventually relented when faced with her determination. They worked together and became lovers. She posed for him and assisted him.

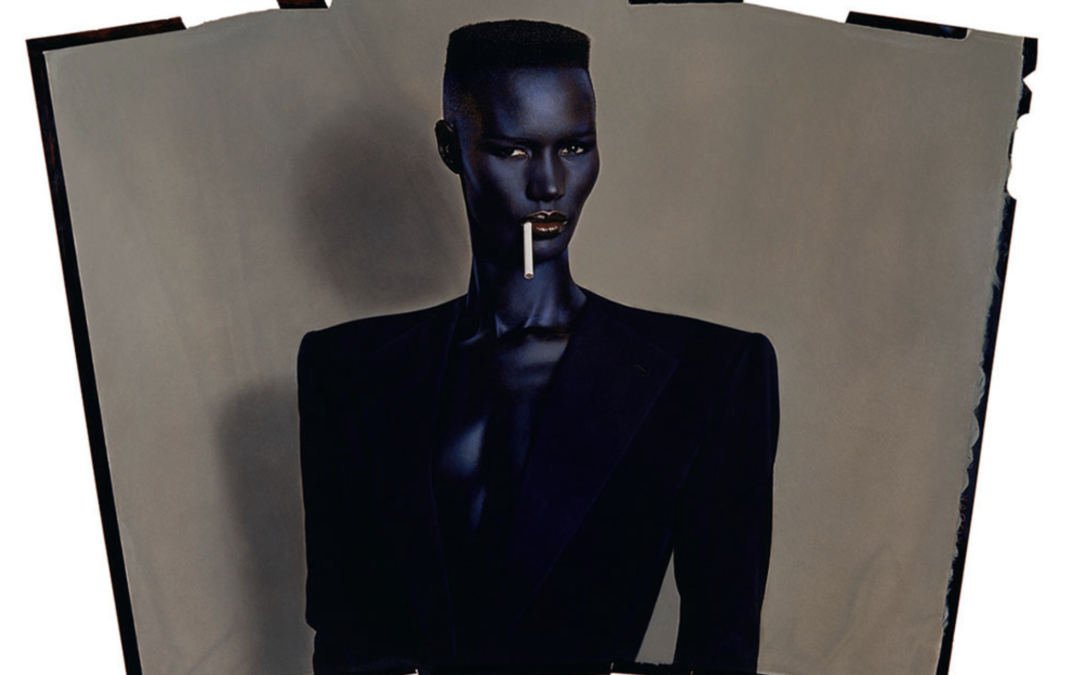

Together they developed solarization, a technique that reverses the negative and positive parts of a photo, and created iconic images (although the credit went to Man Ray alone for a long time). Man Ray later credited Lee for his renewed inspiration at the time.

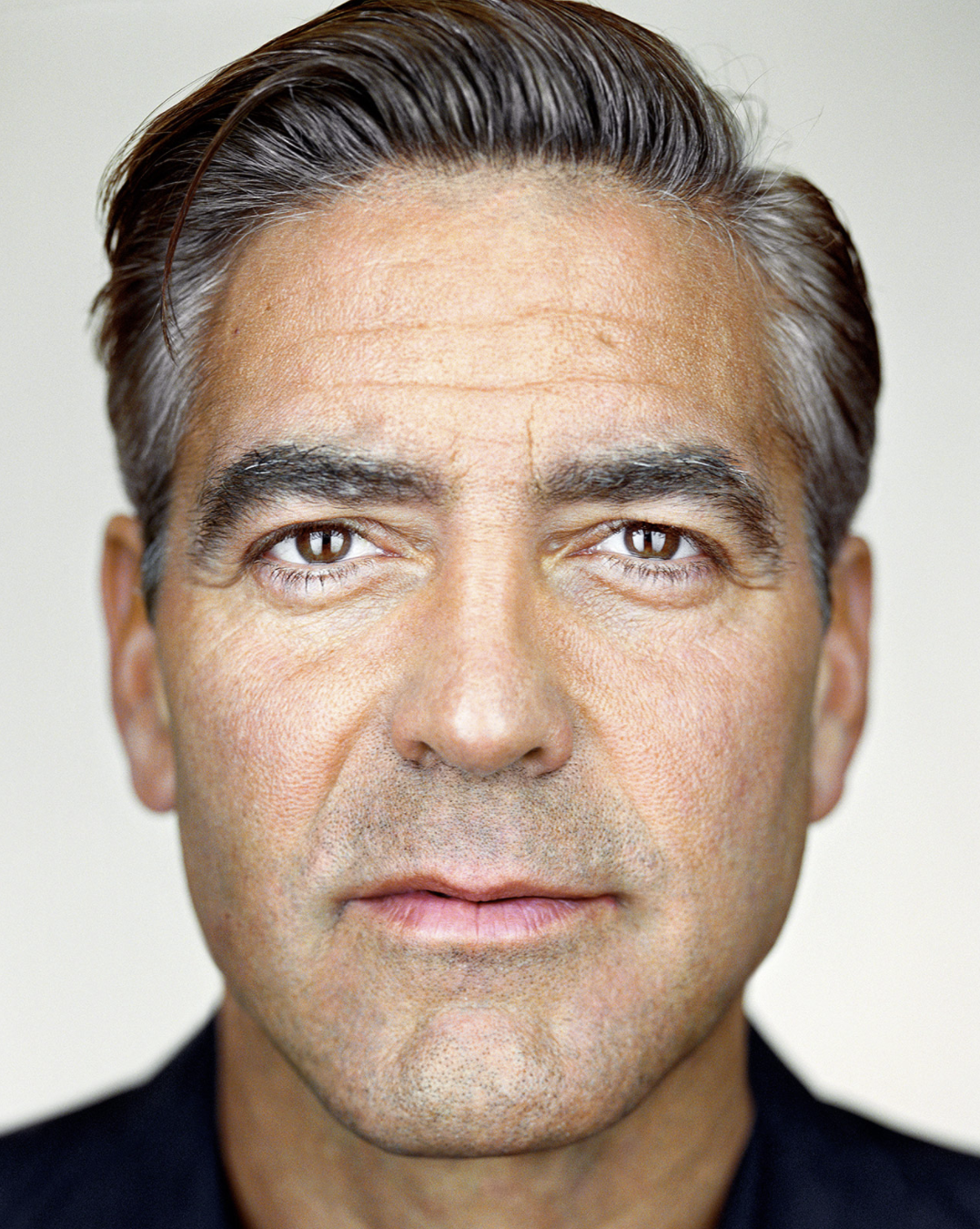

Tired of Man Ray’s jealousy, Lee went back to New York in 1932. She set up her studio with one of her brothers where she photographed celebrity and high society portraits, fashion series, and advertising images, often with a Surrealist edge. She became a sought-after photographer as everyone wanted to have their portrait taken by her. Critics and galleries took notice and her work was featured in a few shows.

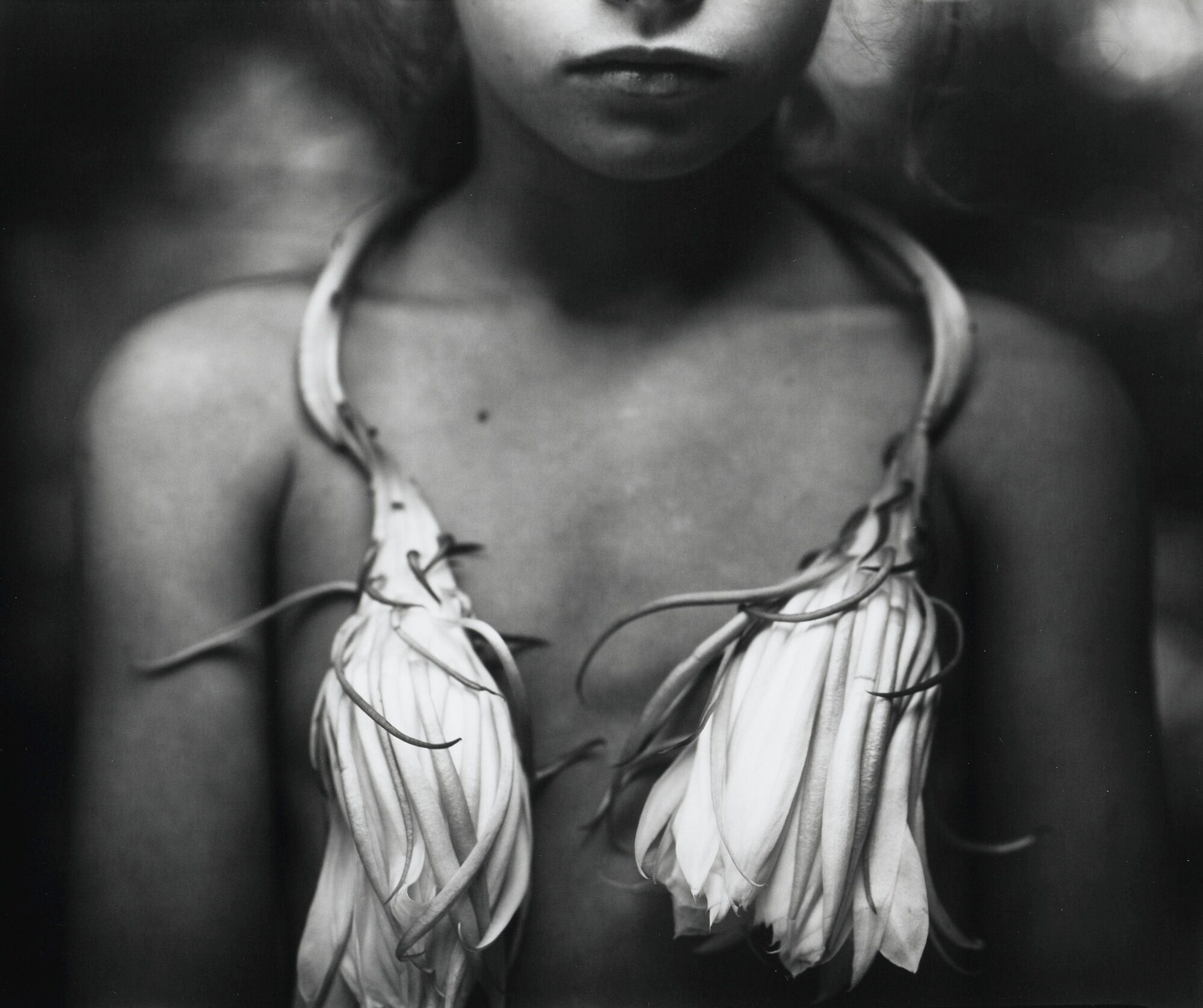

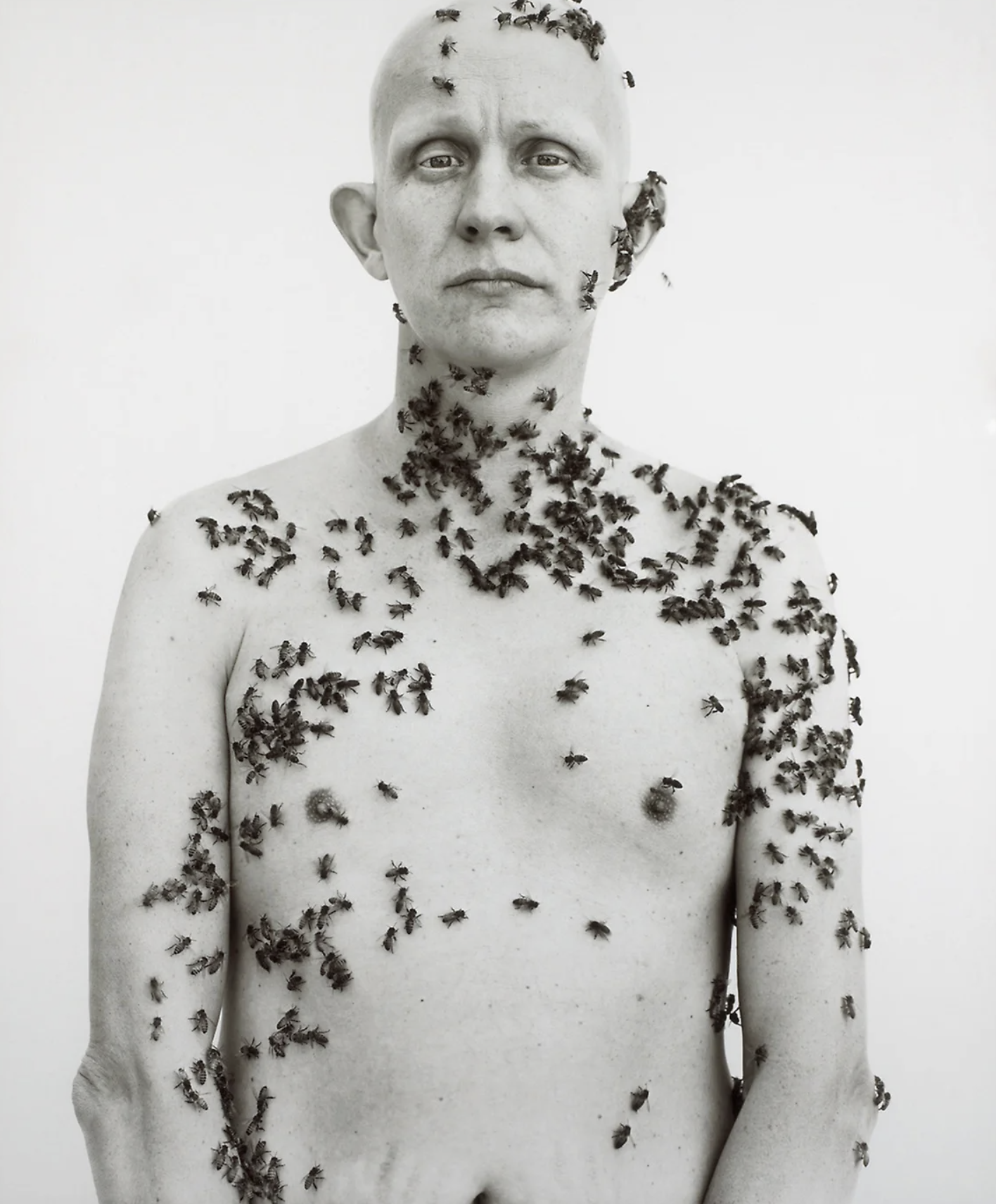

True to form, she didn’t shy away from dark and unsettling subject matters – she once got ahold of a woman’s breast after surgery and photographed it on a plate, like a macabre couple of poached eggs!

WARTIME CORRESPONDENT

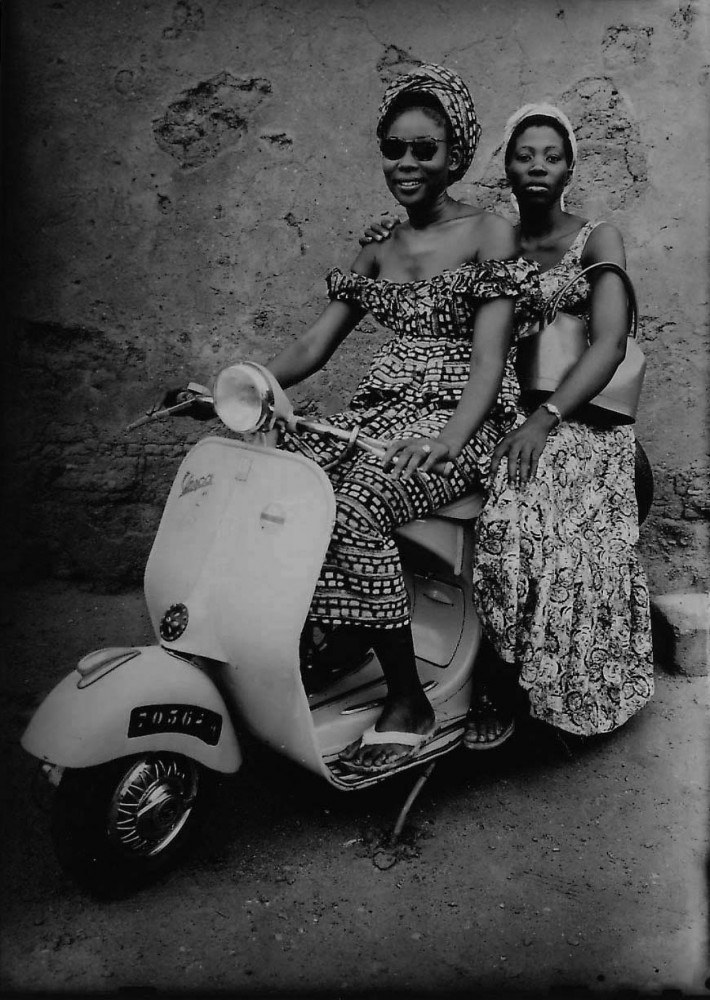

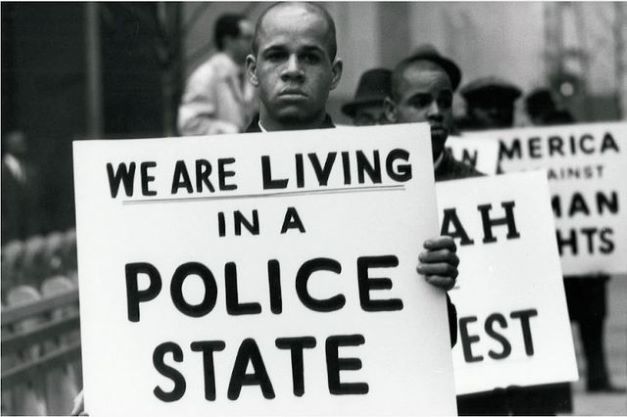

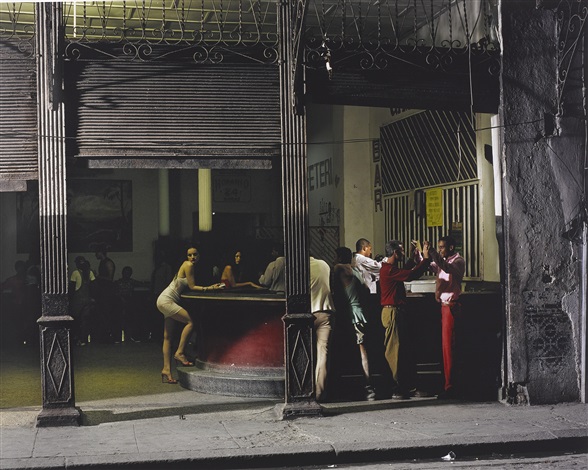

After only two years, Lee married Aizi Eloui Bey, an Egyptian businessman, and moved to Cairo with him. Her work there moved from portraits to landscape and street photography. Ever restless, she traveled to Europe where she reconnected with her artistic circle. She eventually met British Surrealist artist Roland Penrose, whom she became involved with. The beginning of World War II found her now divorced and living in London with Penrose. While other Americans were fleeing to safety back home, she decided to stay in her new adoptive country. She became a prolific contributor of articles and photography for British and US Vogue.

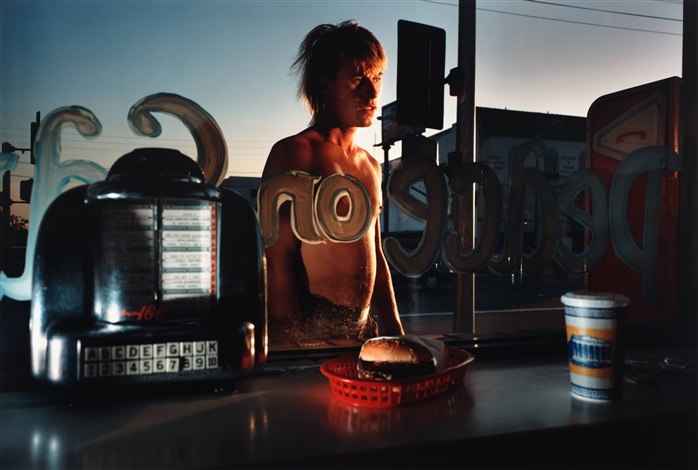

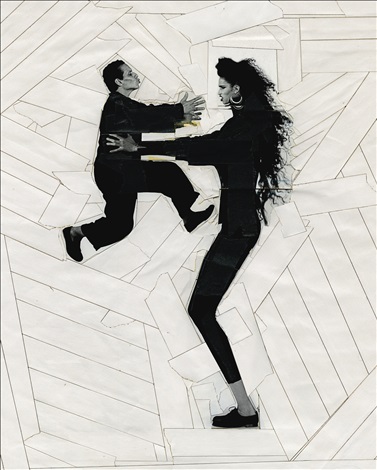

For them, she documented the Blitz and photographed fashion models among bombed-out buildings – a real-life Surrealist moment! The now commonplace images of models in high fashion posing against a backdrop of ruins and desolation owe a lot to Lee’s ground-breaking work. Her reporting transformed the luxury fashion magazines into serious news outlets. Her photographs helped American audiences connect with the horrors and terrors of the war.

Through the Conde Nast publication, Lee was able to get her accreditation as a photographer with the American Army in 1943. Partnering with David E. Scherman, Life Magazine war correspondent, she documented US troops’ victorious march through Europe. Armed with her camera and determination, she became one of the first female war correspondents, and the only one to see combat. In a time when women were often relegated to the sidelines, she stepped into the forefront, challenging gender norms in a male-dominated realm.

"I'd love to be a fashion photographer with a machine gun." Lee Miller

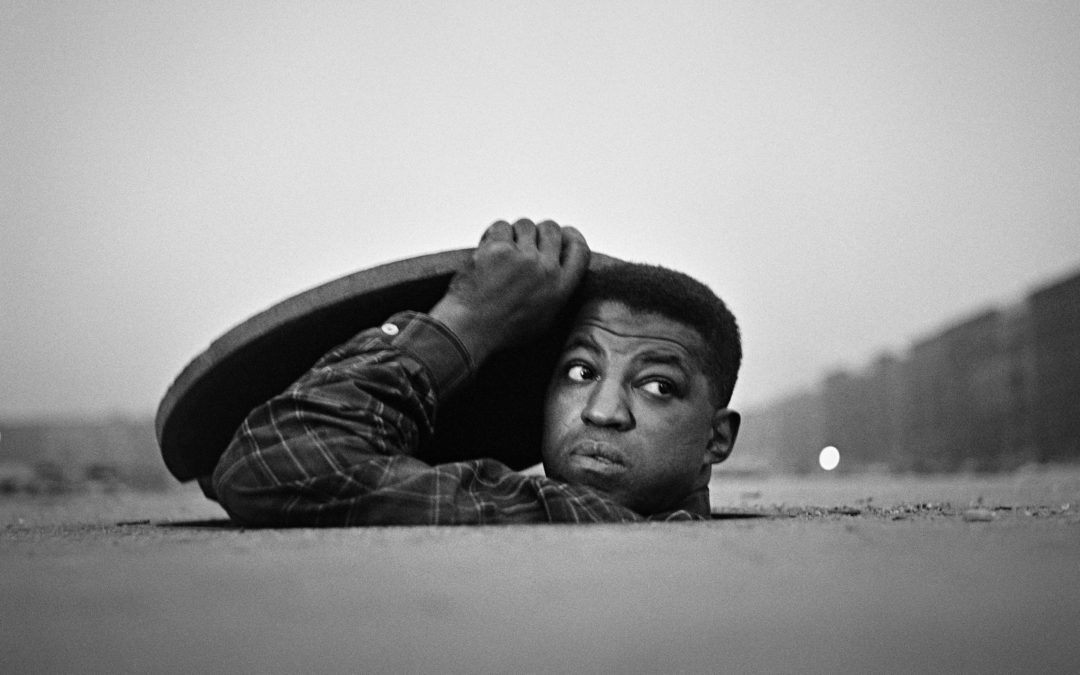

GRITTY REALITIES OF WAR

Her wartime photographs are not just snapshots; they are powerful narratives that force you to confront the stark realities of conflict. Surrealism helped her capture the human folly of war. As Roland Penrose observed, “Her eye for a surrealist mixture of humor and horror was wide open […] The only meaningful training for a war correspondent is to first be a Surrealist – then nothing is too unusual.”

Lee photographed battles, field hospitals and the liberation of concentration camps where she witnessed the horrors of the Holocaust. She traveled through Eastern Europe to photograph the devastating aftermath of the war. She never flinched and held her camera up to bear witness. When few people could or would believe the atrocities committed by the nazi regime, she implored Vogue to publish her images, with a simple message, “Believe it.”

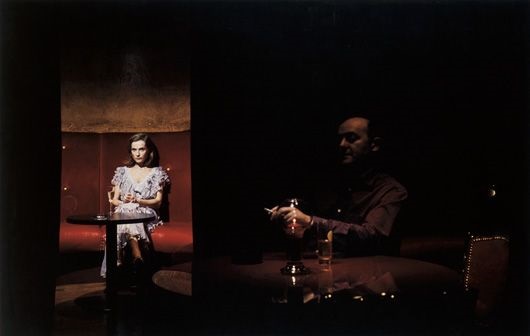

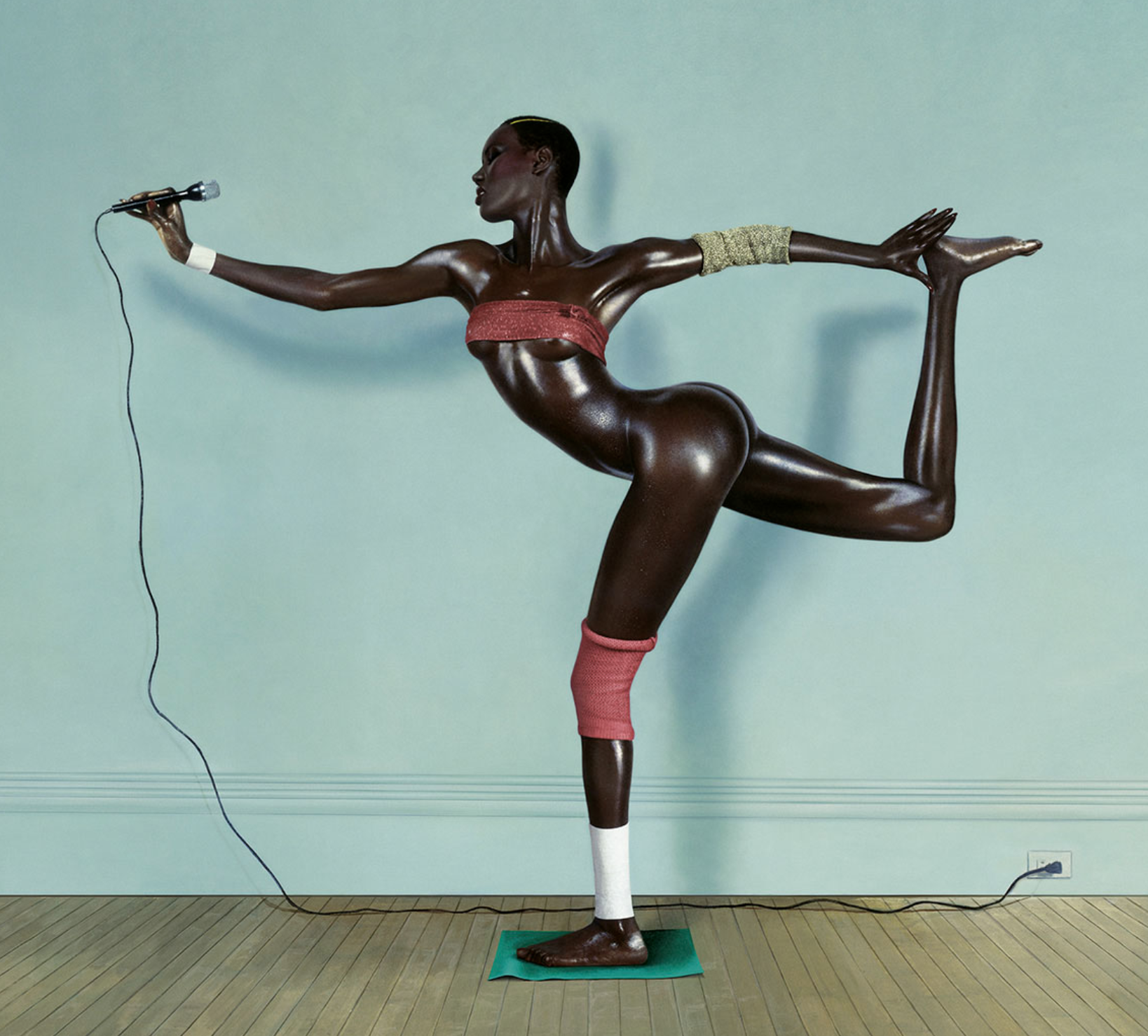

Her most famous photograph is of her taking a bath in Hitler’s private bathroom in Munich right after Germany’s defeat. Taken by Scherman, the image is no mere documentation. Lee craftily set it up, purposefully dumping her dusty combat boots on a white bathmat and placing a small portrait of the defeated nazi leader on the edge of the tub in which she was now bathing. As Lee recalled years later, “I washed the dirt of Dachau off in his tub.” This portrait captures best what Surrealist painter Eileen Agar said of Lee, “a remarkable woman, completely unsentimental and sometimes ruthless.”

POST-WAR LIFE

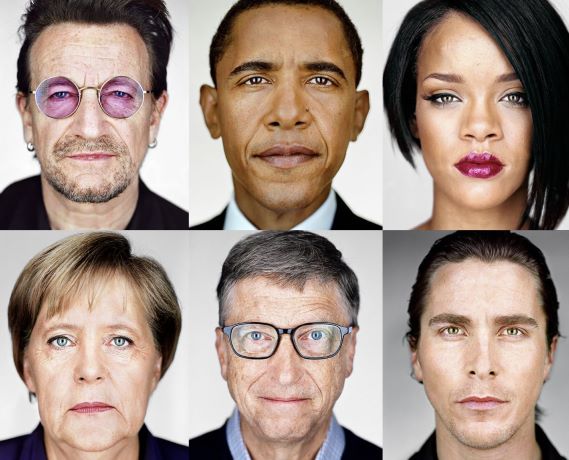

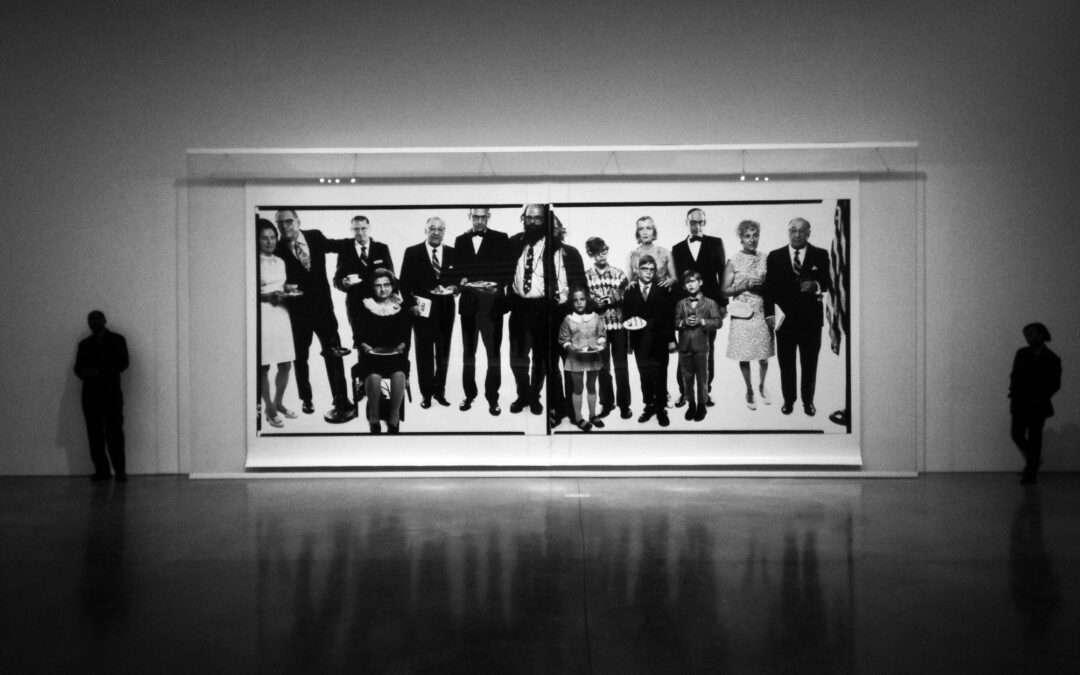

Post-war, Lee lived with Penrose in the British countryside where she ventured further into Surrealism. Her photographs became portals to alternate realities, blurring the lines between dream and wakefulness. It’s not just about capturing an image; it’s about distorting reality and reshaping it into a narrative that demands attention. Her favorite subjects were fellow artists she had met and befriended over the years. Although she stopped working as a professional photographer in the 1950s, she continued photographing her friends, a veritable who’s who of modern art, including Picasso, Magritte, Joan Miro, Max Ernst, or Jean Dubuffet.

She eventually turned her creativity to food. She trained at the famed Cordon Bleu school in London and created surreal dishes, from cauliflower shaped into breasts (with cherry tomatoes for nipples!) to green chicken or blue pasta. Although there’s little documentation about domestic endeavors, there’s no doubt in my mind that they are still part of her Surrealist work. Food became a new venue for her to express herself and question normality.

"I believe in the imagination. What I cannot see is infinitely more important than what I can see." Lee Miller

PERSONAL STRUGGLES

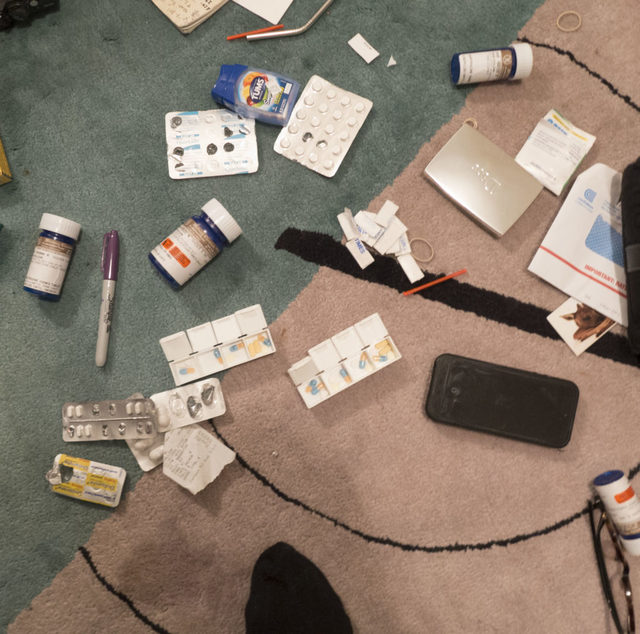

The traumas of her life eventually caught up with her, and she entered a long battle with depression, PTSD, and alcoholism. Although people encouraged her to show her work, she refused and rarely if ever talked about her past. She hid away her photographs and negatives in the attic, as if trying to shut the door to the horror she had been through. Her legendary fearlessness turned into demons that tortured her for the rest of her life.

Her son talks frankly about growing up under the shadow of such an erratic mother. Many in his situation would have turned their back, but true to his mother’s own determination, he decided to try to understand her. After her death from cancer in 1977, the chance discovery of 60,000 old photographs, negatives and documents helped shed light on what his mother had experienced and lived through. He has since made it his life pursuit to share his mother’s legacy and dispel the myth she was just a pretty face.

LEGACY

Lee wasn’t just a witness to history; she was a participant, breaking free from the shackles of society’s expectations. While she was for a long time only seen as a source of inspiration for great male artists like Man Ray or Picasso, she was in fact their equal, using them for her own inspiration as much they did with her. She was no silent muse but very much part of the conversation.

In a way, her life followed the Surrealist view of the world. Like many in her circle, she had very little care for money, marriage and respectability. That freedom was easier for men than for women – yet Lee lived her life as freely as she could, defying society’s expectations and limitations. It’s ironic that her image as a fashion model or muse to 20th century great artists has overshadowed her own artistic achievements, a case of a tree hiding a forest.

© Lee Miller Archives, England 2024. All rights reserved. leemiller.co.uk

Disclaimer: Aurelie’s Gallery does not represent Lee Miller. My “Photographers I love” series is purely for inspiration and to encourage discussion.